The Brontë Parsonage, nestled on the Yorkshire Moors in Haworth, is a magical place. I first went as a Brontë mad A-level student when they opened up the archives for me and, since that early formative experience, I’ve never left it too long between trips.

However, over the past two years it’s been even more special. In 2016 it was the bicentenary of Charlotte Brontë’s birth and last year was the turn of the sisters’ brother, Branwell. This year the focus is on Emily.

Emily Brontë’s great work is, of course, Wuthering Heights, the tragic love story of Heathcliff and Cathy Earnshaw set against the bleak Yorkshire moors, which has found its place as one of the classics of English Literature.

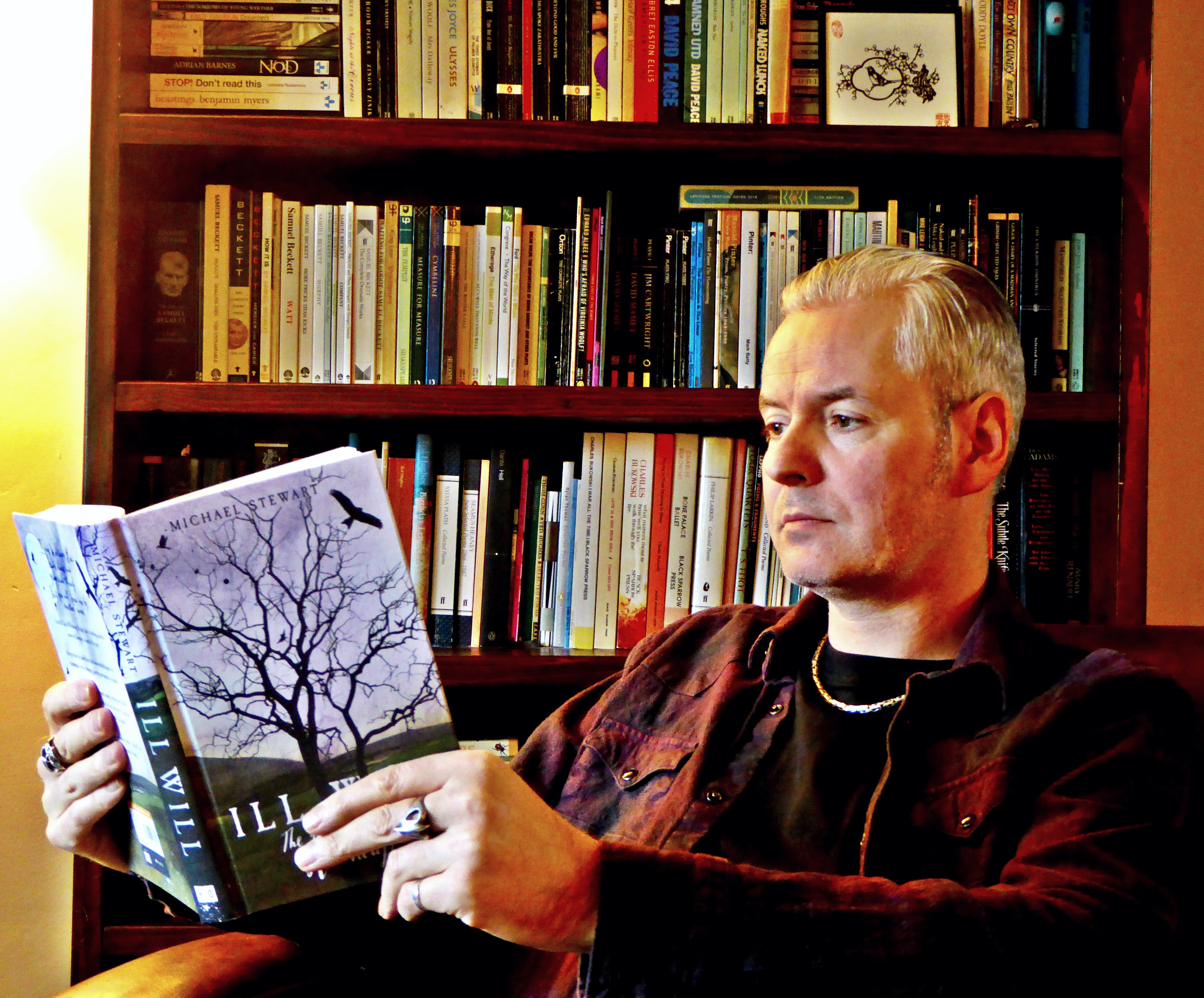

As is fitting for such an occasion, the parsonage has a whole host of events to celebrate the most enigmatic of the Brontë sisters. But perhaps the most exciting for fans eager for a new angle on the ill-fated lovers is the publication of writer Michael Stewart’s new novel, Ill Will.

“Ill Will is a novel about Heathcliff’s lost years,” Stewart tells me. “If you know Wuthering Heights, in the summer of 1780 he hears a conversation where Cathy says it would degrade her to marry him and he runs off in the storm and is missing for three years. When he gets back, he is a changed man – he’s wealthy, he’s a gentleman and he’s a psychopath. My book is about those three years and what happens to make him change.”

It is a brave person who messes with the Brontë legacy. When I attended a Q&A with award-winning writer Sally Wainwright at the launch of her Brontë biopic, To Walk Invisible, one audience member was so outraged that Wainwright had the audacity to put Emily’s poems to music that she literally dropped the mic before storming out. But Stewart isn’t fazed: “You just know certain people will be upset by it and not happy with the portrayal. Everybody has their own idea of who Heathcliff is and you can’t please all the people, you just have to do it. I didn’t give it much thought, I was just absorbed in the writing.”

Nevertheless, as the launch date approaches, it must be a stressful feeling. “You never know what people are going to think about the book. You write something privately and don’t really have many people looking on it.”

Nevertheless, as the launch date approaches, it must be a stressful feeling. “You never know what people are going to think about the book. You write something privately and don’t really have many people looking on it.”

He adds: “A few people have looked at it but, until it goes out there and people start to respond, you don’t know if they will love it, hate it or be indifferent to it. That’s the anxiety I guess. It’s a funny thing we do. You write for yourself and then it goes out there.”

Stewart started life on the other side of the Pennines in Salford but came to Leeds as a mature student in his mid-20s. He has written stage plays, radio plays and short stories. His first novel, King Crow, was published in 2012 winning The Guardian’s Not the Booker prize. He has now settled in Yorkshire, living a stone’s throw from the Brontë’s birth place, so it seems written in the stars that he would gravitate towards tackling this story.

“Actually, it was Kate Bush’s song Wuthering Heights,” laughs Stewart. “I was seven in 1978, and I was drawn to this song and this mad woman on the TV waving her arms around. My mum was doing English O-level at night school and was reading Wuthering Heights. She told me about the story and I was captivated by it. I was too young to read the novel but the story had already intrigued me.”

A lifelong fan of the book, Stewart approached the task at hand seriously.

“I was absorbed in the research,” he explains. “I looked into the social history of the 18th century, the working class, the industrial revolution and rural industry at the time because the Earnshaws are farmers. The main thing was looking at the slave trade in Liverpool which was the main slave port for Europe. I went to the International Slavery Museum, and there’s a fantastic resource at the Central Library in Liverpool, and I looked in the archive at log books, captains’ diaries and letters.”

All this is standard writer research, but Stewart went one step further to understand his characters.

“I walked from Top Withens to Liverpool. Top Withens is a derelict farmhouse on the moors just outside Haworth and is widely regarded as the inspiration for the Earnshaw family home, Wuthering Heights. It’s 65 miles and took me three days. When you think it took Mr Earnshaw three days to get there and back, he was going a bit faster than I was.”

Heathcliff has been portrayed many times, both on screen and on stage, from Sir Laurence Olivier to Ralph Fiennes to, erm, Cliff Richard. With the news that the rights to Ill Will have already been sold, I wonder what the next incarnation of Heathcliff will be like?

“In my book, Heathcliff is 16 or 17 and he’s black, the son of a slave. So, looking at actors now who could play that, it wouldn’t be a big name. What would be nice, if this does come true, is we could champion a new actor in that role.”

It feels as though this new incarnation of Heathcliff will cause a stir and you can’t help but think that the Brontës would approve. They have sat atop suggested reading lists for so long that their texts have become part of the establishment – but it’s easy to forget how revolutionary they were.

It feels as though this new incarnation of Heathcliff will cause a stir and you can’t help but think that the Brontës would approve. They have sat atop suggested reading lists for so long that their texts have become part of the establishment – but it’s easy to forget how revolutionary they were.

“I think Anne certainly, Emily definitely and to a certain extent Charlotte were all politicised,” says Stewart. “They were three female writers, writing at a time there was a certain expectation of what women wrote.”

The Brontës’ writing was produced against a background of isolation and family drama. “It’s a winning formula. You’ve got this parsonage which, at the time, was remote with the moors as a backdrop. The fact that they moved there in 1820 and within a year the mother was dead, and then the two oldest daughters within a year of that. Then the added tragedy 20 years on, Branwell dies first of all, nine months later Emily dies and three months later Anne dies. It’s a tragic and dramatic story.”

It is easy to view the sisters as one, with their novels often being read in conjunction. But scratch the surface and you’ll find three hugely different souls, each looking to have their say from that small house. I wonder which is the Stewart’s favourite?

“It depends. Emily, certainly as a writer, I’m drawn to more. In terms of who I’d be friends with, I don’t think Emily and me would get on. I don’t think she really liked people. I think out of the three sisters, it would be Anne. Anne was the most measured in lots of ways. Charlotte was very ambitious and driven. Emily was very misanthropic, but Anne was more moderate. You’d be able to have a laugh with her.”

Ill Will by Michael Stewart is published by Harper Collins and available to buy now