“Are you English?” asked the guy in the queue. “Yes” I replied. His next question was: “What language do they speak in England?”

This was from someone looking and sounding every inch a sophisticated metrosexual from Hollywood’s West Side.

I’ve accumulated a mushrooming collection of similar stuff that Americans, though of course not my friends, from all walks of life and all ethnicities, have said. It underlines the uncomfortable truth that most Brits know America far better than most Americans know Britain. Ours is an unhealthy, one-sided relationship. If Britain and the US were a couple, a doctor would recommend therapy, lots of it.

At a posh Christmas party I was asked: “Do they celebrate Christmas in England?” “Er, an Englishman, Charles Dickens, helped popularise it”.

Other Europeans have similar tales. A German friend was asked if they had washing machines in Germany. She rewarded her questioner with a lecture on how Germany made the world’s best domestic appliances.

An Italian friend was asked if they had cars in Italy. We came to the slightly charitable conclusion that this was a case of a little knowledge being a dangerous thing. Maybe the woman who asked the question had seen movies of Venice and, knowing it was in Italy, assumed all Italians travelled by water. But hadn’t she heard of Ferrari?

The saying that “War is the way Americans learn geography,” has more than a kernel of truth. Geography is often an American’s weak suit. A visiting British friend, Val, was pounced on by a shopper who, hearing her accent, thought Val could help with a trip to Paris. “Should I make a reservation for the Eiffel Tower? Where should I leave my luggage when sightseeing”? One guy I talked to thought London and England were the same thing.

All the Americans in these stories were from European stock. Less unnerving was the Filipino immigrant who said: “The British don’t have a democracy do they? They have a Queen.” At least she knew we had a Queen and I suspect she knew more about Britain than the average Brit knows about the Philippines. And while Brits can understand American English, some Americans can be truly puzzled by British English and can’t work out what you mean. Slip into British English and life gets taxing. Words pronounced only slightly differently – vitamin, banana, urinal – get blank stares. In the Los Angeles area, where there are so many Latinos, I joke, somewhat lamely, that I now speak two languages. No, not English and Spanish, but English and – pause for effect – American English.

In my first week as an immigrant I got lost, a common occurrence for me, I get lost turning in bed. I couldn’t find our car which I knew was in a car park tantalisingly close. It was unmercifully hot. I was late, I felt nauseous, and disorientated. To top it off, I wanted to go to the loo, desperately. I stopped person after person asking where the car park was. Finally a woman twigged. “Oh you mean the parking lot!’

I’m pretty sure if an American in Britain asked where the parking lot was, the first person they asked would know what was meant.

But then, Brits are brought up on a diet of US movies and television. We become bilingual as children, moving seamlessly between Andy Pandy and Postman Pat, and Tom and Jerry, and Popeye. Otherwise could we contextualise what Americans say? Maybe not.

But then, Brits are brought up on a diet of US movies and television. We become bilingual as children, moving seamlessly between Andy Pandy and Postman Pat, and Tom and Jerry, and Popeye. Otherwise could we contextualise what Americans say? Maybe not.

Brits also have much longer vacations to travel and learn. America has rightly earned its nickname “The No Vacation Nation”.

Many US workers have just one or two weeks holiday a year, and often don’t take off all the time to which they’re entitled. Even travelling to another state can be a big deal, and international travel is largely limited to jetsetters and well-off retirees. William Chalmers in his book, America’s Vacation Deficit Disorder, reckons American’s work-leisure balance is now so severely lopsided that depression is epidemic.

Even Christmas seems to be over in the twinkling of an eye. Here it is straight back to work after Christmas Day, with no time to get over indigestion or play with your toys. It’s a Christmas ritual for me to appeal on Facebook for Americans to adopt Boxing Day.

But when I get frustrated with my new country’s insularity, I take comfort in knowing that not only do many Americans not understand foreigners, they don’t understand each other. This vast and diverse nation is not a melting pot, rather a lumpy stew.

Here language, my sword, my life-long friend, lets me down. Deprived of common expressions, everyday activities can be taxing. But it is the same for many people. And at least my first language is the popular one, English.

And sometimes, just when you feel isolated, little miracles happen. The friend who mentions eating at an Indian restaurant in London’s Drummond Street, a waiter who has been to the Edinburgh Fringe, the film festival audience which claps at the appearance of a British character actor that few Brits would recognise, and the Texan who proudly wears a George Formby T-shirt.

People here are hooked on Downton Abbey, Doc Martin, and Dr Who. I am particularly pleased that so many Americans watch the latter, since I’ve realised the word “Tardis” seems to be a favourite of mine. On hearing my accent, diners in restaurants have shouted out “Benny Hill”.

An acquaintance loves watching Prime Minister’s Question Time and wishes the US has something similar.

Thanks to the last World Cup, more Americans know we call soccer football. I even heard an American announcer use the word “footie”.

And then there was the Mexican electrician who had read that an English soccer club might sign his favourite Mexican player.

“Had I,” he asked, “ever heard of Wigan?”

By Lynne Bateson, US Correspondent

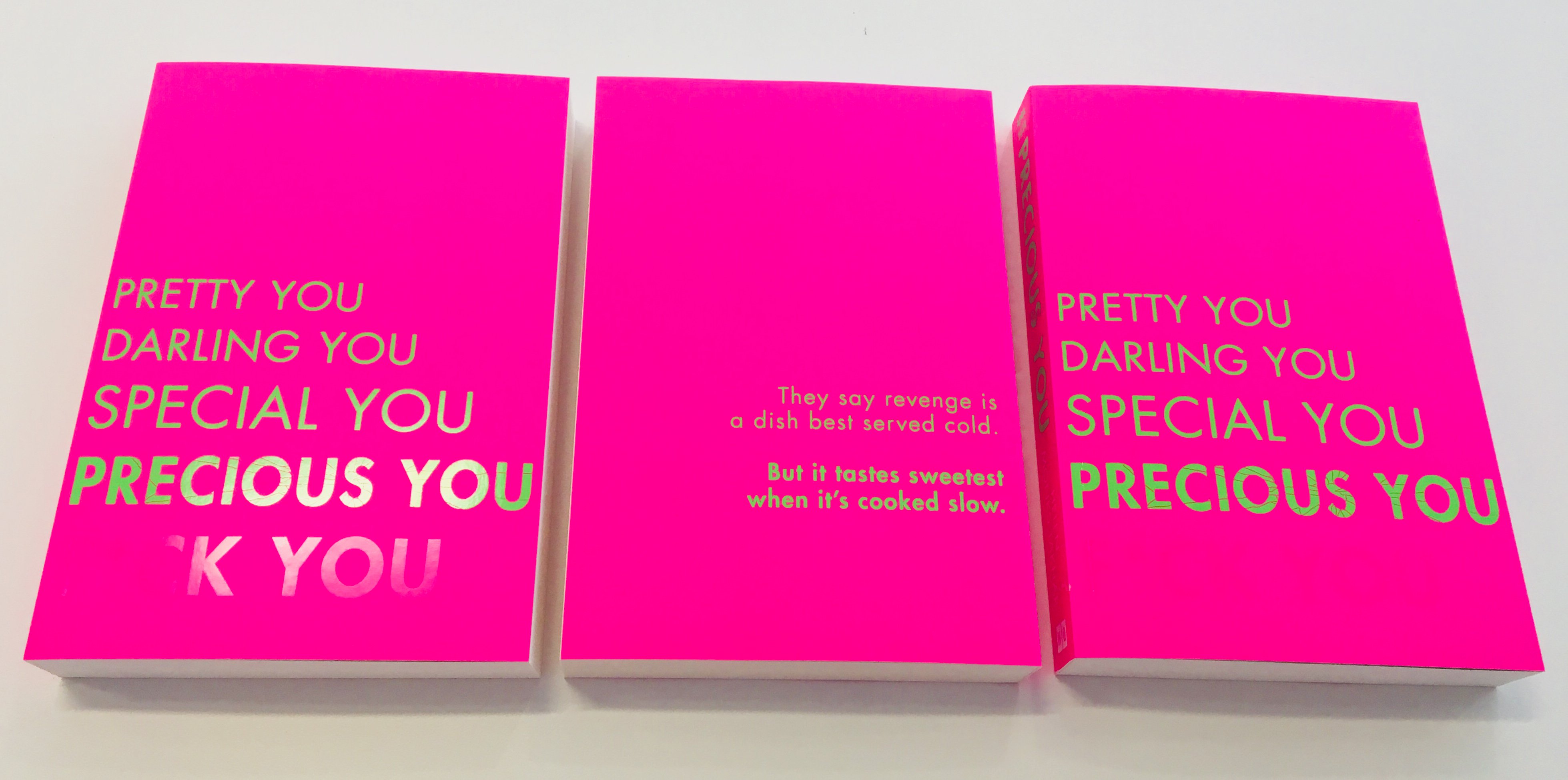

Main image: George Formby

As a child growing up in a Yorkshire village, journalist Lynne Bateson rarely went to the city of Leeds just a few miles away, but she dreamed of living in the US. She made it. Here she recounts her adventures, taking a down-to-earth look at life Stateside.