I remember my first trip to Liverpool well. It was in the late 1980s and I recall seeing a telephone with a lobster for a handset. Oh, and a naked woman embracing a swan.

Surely a trick of the teen mind, you might think. Did the great fallen seaport really touch such depths of lysergic despair?

Naturally, these things weren’t part of the everyday Liverpool streetscape. They were artefacts on display in Tate Liverpool’s opening exhibition in 1988 – a survey of surrealism drawn from the Tate’s own collection. Until then you had to go to London to see such sights but, from that point on, the North was claiming a bit of art action for itself.

Actually, let’s not fall into the trap of pretending our Northern cities were cultural wastelands before London turned up bearing gifts. The great Northern Victorian art palaces had long held collections that lifted the heart and, beyond the established institutions, the North’s contribution to music, literature, theatre, fashion and more was immense.

Tate Liverpool, though, was something new. Here was an institution of international renown acknowledging its debt to the rest of the nation by setting up shop in the Albert Dock – a jaw-dropping maritime relic, newly renovated, but one that just a few years earlier had been a brick-and-iron metaphor for the death of the industrial North. In the early 1980s, its warehouses were collapsing and its waters were clogged up with mud.

Thirty years on, however, it’s gratifying to note that Tate Liverpool’s anniversary exhibition will go under the title Life in Motion. That pre-Tate dock was dead if not quite buried, whereas now it has life coursing through its watery veins.

Thirty years on, however, it’s gratifying to note that Tate Liverpool’s anniversary exhibition will go under the title Life in Motion. That pre-Tate dock was dead if not quite buried, whereas now it has life coursing through its watery veins.

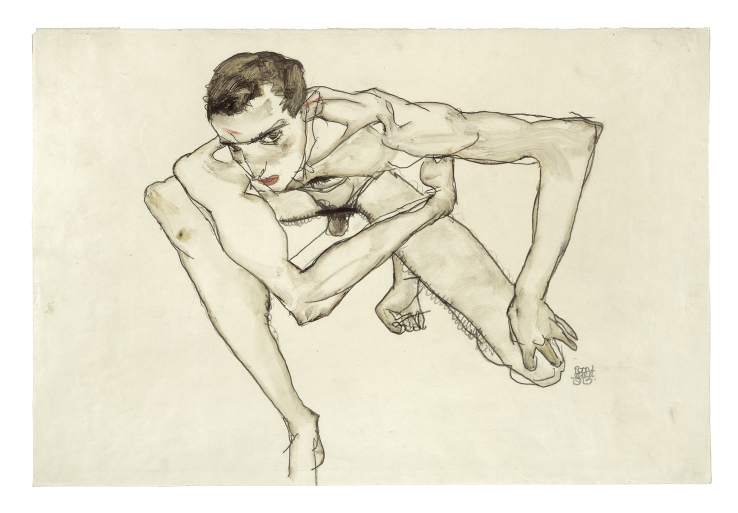

Not that the title refers to the location. In this case, the irrepressible life is locked inside the art of Egon Schiele and Francesca Woodman – he being the celebrated Austrian artist of the early 20th century, and she being the less well-known though no less noteworthy American photographer of the 1970s. As Tate Liverpool marks its three decades on the dock, Life in Motion: Egon Schiele and Francesca Woodman will allow both artists to engage in a delicate celebratory dance.

For Tamar Hemmes, assistant curator at Tate Liverpool, the fact that the artists existed at either end of a century doesn’t mean they aren’t connected.

“These two artists both had a great impact in a short period of time,” she says, referring to their accomplished yet truncated careers (Schiele died in the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic aged 28; Woodman died by suicide in 1981 aged just 22).

“They both created a rich body of work, and both were able to capture brief moments in time. Schiele used very quick marks – he sometimes drew them in a matter of minutes. He created these series of drawings that have the same model in different poses, you can see continuous movement in them. Woodman did the same thing but in a very different way with photography. She used long exposures, and rather than sitting still within that time she would move, so you get a blurred image. It creates a feeling of ‘is she actually present, is she disappearing?’”

“They both created a rich body of work, and both were able to capture brief moments in time. Schiele used very quick marks – he sometimes drew them in a matter of minutes. He created these series of drawings that have the same model in different poses, you can see continuous movement in them. Woodman did the same thing but in a very different way with photography. She used long exposures, and rather than sitting still within that time she would move, so you get a blurred image. It creates a feeling of ‘is she actually present, is she disappearing?’”

So the title is meant literally?

“It refers to both the physical movement and the expressive nature of the human body, as well as psychological movement,” says Hemmes. “What they both do is capture the essence of their subjects, their psychological state, their emotions.”

Ten years ago, Tate Liverpool crowned the city’s European Capital of Culture jamboree with a blockbusting Gustav Klimt show, and there will be echoes of his frank and intimate drawing style in this new exhibition.

“Egon Schiele was a pupil of Klimt,” says Hemmes. “In 1907 he approached Klimt and asked him for advice. He was only 17, just starting out. He’d started at the art academy in Vienna and Klimt became his mentor for a couple of years. He really emulated Klimt’s style.

“But then his work started to become more personal, more expressionist. His figures become quite tortured and there are a lot of emaciated figures. We’ll have some self-portraits in the show, the earliest from 1908 when he was just starting out, and then some from 1909 and 1910. You wouldn’t think they were by the same artist. He begins portraying himself not as an adolescent boy but almost as an older man with lines on his face and very troubled, dark eyes.”

“But then his work started to become more personal, more expressionist. His figures become quite tortured and there are a lot of emaciated figures. We’ll have some self-portraits in the show, the earliest from 1908 when he was just starting out, and then some from 1909 and 1910. You wouldn’t think they were by the same artist. He begins portraying himself not as an adolescent boy but almost as an older man with lines on his face and very troubled, dark eyes.”

Woodman appears as a subject in her own work too, typically less anxious or probing than the twisted and angular Schiele, but much more vulnerable, often naked or just partially concealed.

“She had a very personal approach to the female body,” explains Hemmes. “She shows herself a lot, but also a lot of the women appearing in her works are friends of hers. Sometimes you can’t tell who it is because the face is hidden, but that becomes a thing she plays with. You think it’s always her.

“She had a very short career but created over 800 works. She has been described as someone who was always in motion – not just physical motion, but with her ideas. She described it as having a pan that was overflowing. You get this sense that she was just so inspired by everything around her that she had to keep producing.”

Both artists died at a young age but the exhibition should make clear that they had already reached a rich artistic maturity. How has their influence been felt since their deaths?

“With Woodman, you have artists like Cindy Sherman who were inspired by her work and approach to the human body. And it’s been said that although Woodman tried unsuccessfully to get into fashion photography during her life, it seems she was ahead of her time. A lot of things she does within her work are now quite prominent in fashion photography.

“With Woodman, you have artists like Cindy Sherman who were inspired by her work and approach to the human body. And it’s been said that although Woodman tried unsuccessfully to get into fashion photography during her life, it seems she was ahead of her time. A lot of things she does within her work are now quite prominent in fashion photography.

“Schiele was very controversial during his lifetime, so it took time for artists to really take inspiration from him. But I think his approach to the human body is definitely something that has inspired artists. Tracey Emin has always said she’s inspired by Schiele – not using the same aesthetic, but on an intellectual level.”

This reference to the controversy that tailed Schiele’s career hints at a subject that may well be aired again once Life in Motion opens, namely his approach to sexuality in both life and art.

“With Schiele, you get this male gaze,” says Hemmes. “It’s a man portraying a woman, sometimes in very erotic poses. What’s interesting with him is that you have to think about the context. Vienna at the time was very conservative. The thought of a woman as a sexual being was completely taboo, they were not seen as being able to experience sexual pleasure or anything like that. Schiele was exploring that in his work and said himself he wasn’t creating pornography. He’s saying if you see it that way then that’s what you make of it, but that’s not my intention. I’m making art.

“He was arrested as well and tried for public immorality because children coming into his studio would have seen his artworks. He was heavily criticised for living the life of an artist, but also the fact he was making these types of drawings. His work was really not accepted.”

It will be interesting to see how this aspect of Schiele’s practice sits alongside works created by Woodman, a young woman who grew up during the fiery sexual battles of the 1960s and 70s.

It will be interesting to see how this aspect of Schiele’s practice sits alongside works created by Woodman, a young woman who grew up during the fiery sexual battles of the 1960s and 70s.

“Woodman has been described as a feminist,” says Hemmes. “In the 1970s that was a very prominent thing, and she would have been well aware of that. But some of her works definitely have a degree of temptation and sexuality in them, though I wouldn’t call her works erotic. They’re very different from Schiele’s in that way.”

Visitors will have the chance to judge for themselves from May 24, thirty years to the day since Tate Liverpool first opened its doors. Much has changed in Liverpool since then of course, not least the fact that since this gallery arrived we now take exhibitions of this calibre for granted. Which is just as it should be, to be honest. London may well have given us something good for once, but it’s no less than we bloody deserve.

(Main image: Egon Schiele, 1890-1918 Self Portrait in Crouching Position 1913 Gouache and graphite on paper 323 x 475 mm Moderna Museet/Stockholm)

Life in Motion: Egon Schiele and Francesca Woodman is at Tate Liverpool from May 24 until September 23, 2018. For more information, click here.