Where would we be right now without books? For all my enthusiasm to gobble up the latest series of Brooklyn Nine-Nine or bingewatch The Tiger King (if you haven’t given into the hype, then do so immediately), the only thing that quells my internal anxiety and settles my soul is reading. There’s something reassuring about the weight of a book in my hands and the steady back-and-forth of lines on the page. When we’re feeling clipped and stifled, books allow us to fly.

Northern Soul asked our writers and lots of lovely literary folk for their Best Northern Reads. We kept the criteria simple: a Northern Read can be anything from a Northern writer to a book about the region or even a brilliant publishing company located up North. It’s an eclectic list, one that we hope will inspire you to pick up something new, support the local literary industry but, mostly, offer you some respite from lockdown feels. Here’s Part Two.

Zoe Turner, Verbose Manchester

I read Saltwater by Jessica Andrews while Manchester was burning in the midsummer of last year. My life was changing quickly, my skin was always flushed, I was falling in and out of love, and the passages I pored over were punctuated with city bike rides, exhaust fumes in my throat and grit spitting into my eyes from the pan of Oxford Road. I couldn’t have asked for a better friend to carry with me. This story of a woman who begins in Sunderland and grows out of it in twists, searching for her right to a life distinct from her roots, but not severed from them. I remember reading this novel like I was digging with my hands in soil, pulling out parts of myself with parts of Lucy. I don’t think I’ve ever underlined a book so ferociously.

I read Saltwater by Jessica Andrews while Manchester was burning in the midsummer of last year. My life was changing quickly, my skin was always flushed, I was falling in and out of love, and the passages I pored over were punctuated with city bike rides, exhaust fumes in my throat and grit spitting into my eyes from the pan of Oxford Road. I couldn’t have asked for a better friend to carry with me. This story of a woman who begins in Sunderland and grows out of it in twists, searching for her right to a life distinct from her roots, but not severed from them. I remember reading this novel like I was digging with my hands in soil, pulling out parts of myself with parts of Lucy. I don’t think I’ve ever underlined a book so ferociously.

Damon Fairclough, Northern Soul’s Liverpool Correspondent

I was halfway down the first page of David Peace’s debut crime novel, 1974, when I realised it was a book that would get under my skin.

Describing an early-morning police press conference at Millgarth in Leeds – heavy with the alco breath of newspaper hacks who’ve come straight from the Press Club – Peace writes: “Khalid Aziz at the back, no sign of Jack.”

‘Jack’ was a character I didn’t yet know. But Khalid Aziz?

‘Jack’ was a character I didn’t yet know. But Khalid Aziz?

The line plunged me deep into my mid-70s childhood, prostrate on the carpet watching Look North on the telly. Post-tea, pre-homework, Look North was (and still is) the BBC’s early evening news programme for Yorkshire. Khalid Aziz was a regular presenter, a local TV journalist who we all came to know, but whose name – 30 years on – hadn’t troubled my consciousness for decades.

It was a detail that confirmed that this time and place – the West Yorkshire of the mid-70s – wasn’t just a convenient backdrop against which a conventional crime plot would play out. This book – and the three subsequent titles in the series: 1977, 1980 and 1983 – is temporally and regionally specific, building on events inspired by the real-life Yorkshire Ripper saga to create a glowering, rain-sodden, parallel-universe of a Yorkshire in which someone forgot to turn on the light.

Reading these books (published between 1999 and 2002, and now marketed as the Red Riding Quartet) is like receiving a thick belch of fag-smoke in the face. I know there are other literary Norths but this is my favourite – a North that reeks of Ford Escort fumes, Formica and sin.

Emma Yates-Badley, Northern Soul’s Literary Editor

‘Have you ever read a book that left you astounded?’ That’s how I began my review of Slip of a Fish, the 2018 Northern Book Prize winner by newcomer Amy Arnold, and I stand by that statement. While its scant detail and confusing narration might not be everyone’s cup of tea (I’ve tried to push this book onto multiple people and haven’t always been successful), it’s a mesmerising piece of fiction.

‘Have you ever read a book that left you astounded?’ That’s how I began my review of Slip of a Fish, the 2018 Northern Book Prize winner by newcomer Amy Arnold, and I stand by that statement. While its scant detail and confusing narration might not be everyone’s cup of tea (I’ve tried to push this book onto multiple people and haven’t always been successful), it’s a mesmerising piece of fiction.

Slip of a Fish, published by Sheffield-based And Other Stories, is an enigma. It seems to be about one thing and then it’s another and then it’s not about that at all. The narrative morphs and deflects, baffling the reader. You emerge feeling foggy-headed as though rousing from a dream you can’t quite make out. It’s a beautifully written novel, almost lyric in its cadence, but the words are flimsy and difficult to keep in the palm of your hand. I couldn’t stop thinking about it long after I’d read the last line. I’m still thinking about it, even now.

Adam Farrer, The Real Story

Reading Jenn Ashworth’s non-fiction always leaves me feeling as if it’s making me into a better writer. There is something fearless about it, leading by example and demonstrating exactly how bold and exposing you can be if you allow yourself to be as daring as her. Take the opening essay of her collection Notes Made While Falling, an unflinching account of medical trauma that, as a reading experience, is not unlike being simultaneously slapped across the face and punched in the chest. The rest of the collection goes on in this way, full of trauma, itchy obsessions and crumpled memories that all have a transformative impact. It expertly covers so much varied ground that opening it up feels like lifting the lid on a bubbling pot in Willy Wonka’s factory. ‘Oh that,’ he’d say, as you stare into its multi-coloured contents. ‘That’s the soup that tastes of everything.’

Reading Jenn Ashworth’s non-fiction always leaves me feeling as if it’s making me into a better writer. There is something fearless about it, leading by example and demonstrating exactly how bold and exposing you can be if you allow yourself to be as daring as her. Take the opening essay of her collection Notes Made While Falling, an unflinching account of medical trauma that, as a reading experience, is not unlike being simultaneously slapped across the face and punched in the chest. The rest of the collection goes on in this way, full of trauma, itchy obsessions and crumpled memories that all have a transformative impact. It expertly covers so much varied ground that opening it up feels like lifting the lid on a bubbling pot in Willy Wonka’s factory. ‘Oh that,’ he’d say, as you stare into its multi-coloured contents. ‘That’s the soup that tastes of everything.’

Helen Nugent, Editor of Northern Soul

The Manchester Man by Mrs G. Linnæus Banks is not the best novel to come out of the 19th century’s industrial North. I mean, it’s no North & South or Jane Eyre. But I defy you not to fall in love with it.

The narrative of Isabella Banks’s 1876 novel follows the story of Jabez Clegg, the ‘Manchester Man’ of the title, mirroring the economic growth of the city during the early 1900s and vividly portraying the Corn Law riots and the Peterloo Massacre of 1819. Although the novel isn’t terribly well known now, it was popular in its day. Like much of Charles Dickens’ work, it was serialised in 19th century magazines and, for a time at least, Banks (who, as was the tradition, published under her husband’s name) was a celebrated author.

I suppose it would be fair to say that Banks’s book is a bit of a pot boiler. It charts Jabez’s rise to local prominence as well as his complex and melodramatic love life. People are killed off with abandon and the plot twists and turns with alacrity. It begins with a flood (a real event in Manchester’s past) and a rousing first few sentences: When Pliny lost his life, and Herculaneum was buried, Manchester was born. Whilst lava and ashes blotted from sight and memory fair and luxurious Roman cities close to the Capitol, the Roman soldiery of Titus, under their general Agricola, laid the foundations of a distant city which now competes with the great cities of the world.’

I suppose it would be fair to say that Banks’s book is a bit of a pot boiler. It charts Jabez’s rise to local prominence as well as his complex and melodramatic love life. People are killed off with abandon and the plot twists and turns with alacrity. It begins with a flood (a real event in Manchester’s past) and a rousing first few sentences: When Pliny lost his life, and Herculaneum was buried, Manchester was born. Whilst lava and ashes blotted from sight and memory fair and luxurious Roman cities close to the Capitol, the Roman soldiery of Titus, under their general Agricola, laid the foundations of a distant city which now competes with the great cities of the world.’

Don’t be put off by that wordy beginning though. Consider, perhaps, the beauty of this excerpt from the novel, which can be found on Tony Wilson‘s gravestone in Southern Cemetery:

‘Mutability is the epitaph of worlds

Change alone is changeless

People drop out of the history of a life as of a land

though their work or their influence remains.’

Lucie McNight Hardy, author of Water Shall Refuse Them

Hebden Bridge-based Bluemoose Books is publishing a treasure trove of novels by women in 2020. The first, and the one I’m most excited about, out on April 30, is Anna Vaught’s Saving Lucia, a captivating tale of four extraordinary women, incarcerated, their voices not heard. Until now. They are Lady Violet Gibson, would-be assassin of Mussolini; Lucia Joyce, daughter of James; Anna O and Blanche Wittman, the latter of whom both helped to shape the course of psychoanalysis.

Hebden Bridge-based Bluemoose Books is publishing a treasure trove of novels by women in 2020. The first, and the one I’m most excited about, out on April 30, is Anna Vaught’s Saving Lucia, a captivating tale of four extraordinary women, incarcerated, their voices not heard. Until now. They are Lady Violet Gibson, would-be assassin of Mussolini; Lucia Joyce, daughter of James; Anna O and Blanche Wittman, the latter of whom both helped to shape the course of psychoanalysis.

Vaught crafts distinctive voices for these women, and her careful research pays off, each character brought considerately to finely painted life as they embark on a journey of the imagination, a road trip of alternative realities. The prose flits and meanders, deviates and accelerates, reflecting their varying mental states as the women relate their stories. Gorgeous imagery draws on nature and art, and playful references to Beckett and Joyce abound. A fascinating and challenging book which allows the reader the remarkable privilege of hearing from women who were previously not given a voice.

Sarah Jasmon, author of You Never Told Me and Summer of Secrets

Martine Bailey writes historical fiction, described by Fay Weldon as ‘Culinary Gothic,’ and her stories sweep you into a compellingly real Georgian world complete with intrigue, con-artistry and the most mouth-watering recipes. Born near Manchester and now based in Chester, Bailey also brings a powerful sense of the North to her writing, a welcome change in a time period more often fixated on London and Bath.

Martine Bailey writes historical fiction, described by Fay Weldon as ‘Culinary Gothic,’ and her stories sweep you into a compellingly real Georgian world complete with intrigue, con-artistry and the most mouth-watering recipes. Born near Manchester and now based in Chester, Bailey also brings a powerful sense of the North to her writing, a welcome change in a time period more often fixated on London and Bath.

The difficulty is deciding which book to choose. I’m going with her second, The Penny Heart. We’re in Manchester, 1787. Michael Croxon is looking to make his fortune, transfixed by ‘half-built skeletons of factories and mills, the lofty temples to the new religion of commerce’. He falls victim to a swindle, but it’s Mary Jebb – a ‘bold woman…shameless’ – who is sent to Newgate and then deported. Hold tight as she makes her way back to England, and Croxon’s’s new Lancashire home, intent on revenge.

David Coates, Events Manager at Blackwell’s Manchester

I read Ironopolis by Glen James Brown more than a year ago now and it has stayed with me ever since. Shortlisted for the Portico Prize, Ironopolis is a stunning debut made up of six interweaving stories. It’s set on a Middlesbrough housing estate and focuses on the lives of three generations of working class families who live there – each chapter slowly reveals more about their histories and how they entwine (and are affected by the legend of the mysterious Peg Powler).

I read Ironopolis by Glen James Brown more than a year ago now and it has stayed with me ever since. Shortlisted for the Portico Prize, Ironopolis is a stunning debut made up of six interweaving stories. It’s set on a Middlesbrough housing estate and focuses on the lives of three generations of working class families who live there – each chapter slowly reveals more about their histories and how they entwine (and are affected by the legend of the mysterious Peg Powler).

All the characters are brilliantly realised and written with real warmth, even when they go to some very dark places. A truly fantastic book filled with both violence and humour that not only tells a great story but has important things to say about class, family and place. Highly recommended.

A.F. Stone, author of The Raven Wheel

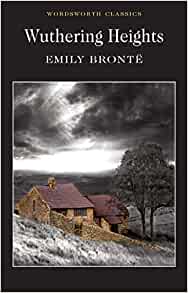

I’m struggling to articulate how much this book means to me. I first read Wuthering Heights when I was about 14 (the perfect age to do so – if you have teenagers in lockdown, get them on it). I remember being unable to stop reading, despite the fact that I had to get up for school the next day. In particular, I vividly recall that one passage had me crying inconsolably at about 3am. That’s probably when I decided literature was what I wanted to pursue, somehow. It’s been a pivotal influence for me as a writer.

I’m struggling to articulate how much this book means to me. I first read Wuthering Heights when I was about 14 (the perfect age to do so – if you have teenagers in lockdown, get them on it). I remember being unable to stop reading, despite the fact that I had to get up for school the next day. In particular, I vividly recall that one passage had me crying inconsolably at about 3am. That’s probably when I decided literature was what I wanted to pursue, somehow. It’s been a pivotal influence for me as a writer.

Wuthering Heights is dark, raw, and cruel. It explores the legacies of abuse and neglect through generations. The natural landscape is a crucial character, all of its own. It evokes empathy and compassion. In short, it’s Northern writing at its best and everything that my work aspires to.

Catherine Taylor, freelance writer and editor of The Book of Sheffield: A City in Short Fiction

I grew up in South Yorkshire and the book most associated with that area is Barry Hines’ classic A Kestrel for a Knave, made into the unforgettably raw 1969 film, Kes. Yet one of my favourite (if ‘favourite’ is the right word) Northern books is Pat Barker’s brave and customarily gritty second novel Blow Your House Down, published in 1984 (Virago Modern Classics). The book is set in in a town which might be Bradford, West Yorkshire, where a serial killer stalks the dank night streets, attacking and murdering sex workers.

I grew up in South Yorkshire and the book most associated with that area is Barry Hines’ classic A Kestrel for a Knave, made into the unforgettably raw 1969 film, Kes. Yet one of my favourite (if ‘favourite’ is the right word) Northern books is Pat Barker’s brave and customarily gritty second novel Blow Your House Down, published in 1984 (Virago Modern Classics). The book is set in in a town which might be Bradford, West Yorkshire, where a serial killer stalks the dank night streets, attacking and murdering sex workers.

It is presumably based on the terror inflicted by Peter Sutcliffe, aka the Yorkshire Ripper, who was finally caught by police in early January 1981 following years of botched investigations, with the blame firmly centred on his victims. Sutcliffe happened to be arrested in the lane behind my school in Sheffield. Barker’s book is set in a late 1970s Northern England of boarded-up shops, dismal factories and dingy, sinister street lighting. Her characters, a group of very different women, are vivid and unforgettably drawn. While she remains best known for her later World War One-set Regeneration trilogy, the final novel of which won the Booker Prize, it is the feminist and frank Blow Your House Down, buzzing with the vitality and futility of women risking their lives out of economic necessity, which remains the most memorable to me.

Compiled by Emma Yates-Badley, Literary Editor